How Long? Not Long!

|

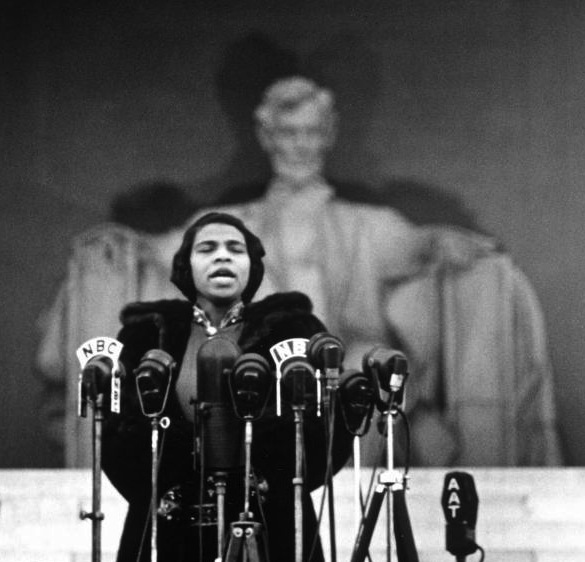

| International opera star Marian Anderson singing at the Lincoln Memorial. |

While chatting with soprano Lowri Marie on set at the MNN studios, she told the story of being recommended by her white high school voice teacher to audition for the Arkansas All-State Choir. Granted the choir was all-white at the time, but Lowri’s teacher felt that her voice was exceptional enough to overcome the race barrier. So she followed her teacher’s advice and went to the audition. Following the auditions, concerts were presented by both the All-State Choir and the Alternate Choir, which was made up of singers who did not make the All-State Choir at the auditions. Lowri sang in the Alternate Choir concert. When she returned, her teacher enthusiastically congratulated her for making it into the All-State Choir, and asked how the concert went. Lowri then told her that she sang in the Alternate Choir. The teacher was confused. “No!” she exclaimed. “I was informed you made it into the All-State Choir!” Then she turned bright red when she realized that Lowri was not allowed to sing in the Arkansas All-State Choir because she was black.

During our taping at MNN I asked Lowri how she thinks that experience has affected her. She sat for a while, and finally said that she really hadn’t thought about that experience because young blacks at that time were pressured to just get over it, and not dwell on negative experiences or rejections handed out by whites. So she moved on, eventually pursuing a career in veterinary medicine. And now, fifty years later, she is finally pursuing her dream of becoming an opera singer.

Her story reminded me of stories told to me by my parents. My mother as a teenager had been engaged to appear as piano soloist with the Charleston, West Virginia Symphony Orchestra. She would have been the first black woman to be so honored. A few weeks before the concert, the conductor who had engaged her died of a heart-attack. His replacement was so racist that he cancelled my mother’s contract. I don’t think she ever got over that heartbreak, in spite of the fact that thirty-five years later, her daughter would become the first black female (I was still a child at the time) to appear as piano soloist with the Nashville Symphony.

Then my father told the story of how his white piano teacher in Americus, Georgia would have him enter her house from the back door, because she didn’t want the neighbors to see that she had a black student. Then, when all of her students and their parents would gather in her home for semi-annual recitals, my father and his mother would sit and wait in a back room “… in cramped quarters,” for his turn to come out and play. Little Matthew already had his own radio show, so the teacher would announce his performance as a special surprise. This was how she justified keeping him hidden away from the others. His stage name at the time was “Sunshine,” a name he acquired at the segregated movie theater where he played the organ to accompany the silent films, dressed in a bell-hop uniform.

No one has really studied the psychological impact of such traumas. As a boy, my father knew of men who had been lynched. My mother, whose father was a surgeon, had to walk passed two white public schools to get to the colored public school, because white communities were built around her father’s house long after he had built his own home. When I was faced with my first encounter (that I was aware of) with racism, my parents made it clear that they couldn’t hear about it. I didn’t know if it was because they didn’t want me to dwell on it, or because it was too painful for them to hear about. As a result, I learned to keep such experiences to myself.

When I was in elementary school – say, 5th or 6th grade – I made a friend at the beginning of the school year, a little white girl who would sit with me to have lunch, and hang out with me in the halls between classes. Our friendship developed for a few weeks. Then one day she approached me in the hall with a horrified look on her face. “What’s wrong?” I asked. In all seriousness she said, “Someone told me you were a nigger!” I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know whether or not she knew that “nigger” was the wrong word for a “black person.” It was clearly a word she had heard in her parents’ house. At the time, I didn’t have the language to say, “That word is inappropriate,” etc. So I just shrugged. Judging from the shock on her face, one would have thought that I had just told her that I was a leper. She shook her head and whispered “No!” then walked away. Later when I saw her in the hall and waved hello, she pretended she didn’t see me. She never spoke to me again.

This experience was especially painful because the black girls at my school, for the most part, were very rough on me. They called me “white girl,” or “yella,” and ridiculed my correct speech. I couldn’t figure out why they hated me so much. They accepted other light-skinned girls into their ranks who spoke the same slang or Ebonics as they did. But I wasn’t allowed to talk like that around my parents. I rarely even heard it spoken, except at school. So when this little white girl – who was being bused to our school from the other side of town – wanted to be my friend, I was happy. To this day I still haven’t fully explored the psychological impact of that experience

Professionally, I did have experiences in the South where racist jurors for piano competitions would not allow me to play the repertoire I had prepared, and were clearly in a rush to get me off of the stage. Others certainly noticed that this was happening, but no one did anything about it. Some well-meaning whites would shake my hand and tell me, “You’re so talented,” but talent alone wasn’t enough to win one of the prizes, evidently. Even now I sit and watch while white boys secure the contracts that should be mine.

|

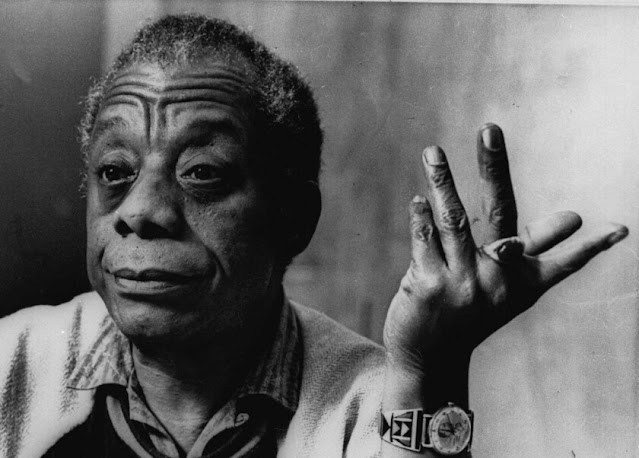

| Eleanor Roosevelt with Marian Anderson |

Everyone knows that the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to allow famed contralto Marian Anderson to sing at Constitution Hall in our nation’s capital, and as a result she gave her historic concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. That audience became the first integrated audience in Washington, DC, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the DAR after this incident. I’ve often wondered why the white women of the DAR could be so hateful. Was it because they blamed black women for their husbands’/fathers’ infidelities? Was that why they insisted that black women be seen as nothing more than servants? Opera houses all over the world had welcomed Miss Anderson to their stages, but her own country treated her like dirt. And this was thirty years before Lowri Marie's incident with the Arkansas All-State Choir!

Martin Luther King Jr. said: “How long? Not Long! Because no lie can live forever!” Well this lie has lived for long enough!

Comments

Post a Comment