Ebony and Ivory: A Dissonant Truth

|

| Clara Schumann (née Wieck) on a 100 Euro note |

As some of you know, I am preparing for a Carnegie Hall concert in the near future; so recently my attentions have turned to other pianists who have enjoyed successful concert careers. While reading a biography of pianist/composer Clara Schumann*, I was filled with pangs of jealousy. Her father, Friedrich Wieck, was a shrewd businessman. He booked all of her concerts, negotiated her fees, and devoted himself to her publicity. Granted, little Clara didn't have much of a childhood; but neither did I. Her parents divorced when she was five, and her father demanded sole custody.

|

| Clara Wieck at age 15 |

Clara's father owned and ran a piano dealership, and was determined that his daughter would be known throughout Europe as a wunderkind, as young Mozart had been. But Friedrich Wieck did not have to worry about being discriminated against because of his race. He was free to build his daughter's career however he imagined it. She was already a superstar long before she married composer Robert Schumann at age nineteen. At that time, marriage to a man was the only way she could escape her father's stranglehold on her life. Her father fought against the marriage in the German courts. She even had to sue her father for the proceeds from her concerts, which he had confiscated.

|

| Friedrich Wieck, Clara's father |

Sadly, on the day of her marriage, Clara went from a tyrannical father to an opportunistic husband. Robert Schumann had already injured his hand before they married, so he counted on Clara to premier and perform his compositions. Her fame and career continued well after her husband's death. (Keep in mind, she had to support their eight children.) Though she was a major figure in the European concert world for most of the 19th century, she was hardly mentioned during my studies at Juilliard and Curtis.

|

| Robert Schumann, Clara's husband |

My Juilliard piano teacher William Masselos loaned me a book of correspondence between Clara and Johannes Brahms, which I couldn't put down. Their correspondence reminded me that there was no man negotiating on my behalf when I had given my New York Debut. My father was busy with his teaching position at Fisk, and with directing and securing engagements for the Fisk Jubilee Singers. But deep down, he hoped that a white man would come along and do for me what he was unable to do in the white-male-dominated classical music world. My mother socialized with the white members of the symphony board and the Women's Advisory Board of the Tennessee Performing Arts Center, but she was still unable to stir up enough interest in my career among whites - in spite of the fact that I had appeared as piano soloist with the Nashville Symphony at age thirteen. Perhaps the pain of her own disappointments because of racism was too fresh. Perhaps she projected her own experience onto mine. Early in my young adulthood it became clear to me that my parents could not provide the kind of support I would need to launch a lucrative career. I was on my own.

My parents were able, however, to secure concert engagements for me via their contacts within the black community. Audiences at HBCU's loved my concerts and supported my music, but blacks in large numbers did not sit on the boards of symphony orchestras or concert series. When concert impresario Sol Hurok swore that white classical music audiences would never accept blacks on the stage, why on earth would my parents force me into this field? Did they think I was light-skinned enough to be accepted by whites? Or did they hope that enough time had passed for attitudes to change? Well, regardless of how light-skinned I was, I still needed a father (or husband, which would not happen) who would intervene on my behalf. I sometimes wonder if my father didn't want these white organizations to know that my father was black. So, in his mind, I was supposed to magically overcome centuries of racism and sexism single-handedly. The word "delusional" comes to mind.

|

| Don Shirley, subject of Green Book |

Pianist Don Shirley, subject of the recent film Green Book, was not allowed to have a concert career because of his race. Sol Hurok demanded that he play jazz, so Shirley traveled the world with his jazz trio, occasionally incorporating classical melodies and style in his arrangements. I heard Shirley and his trio perform in concert at Fisk University when I was a child, then played his nine-foot concert grand in his apartment here in New York after the Fisk Jubilee Singers performed at Carnegie Hall under my father's direction.

|

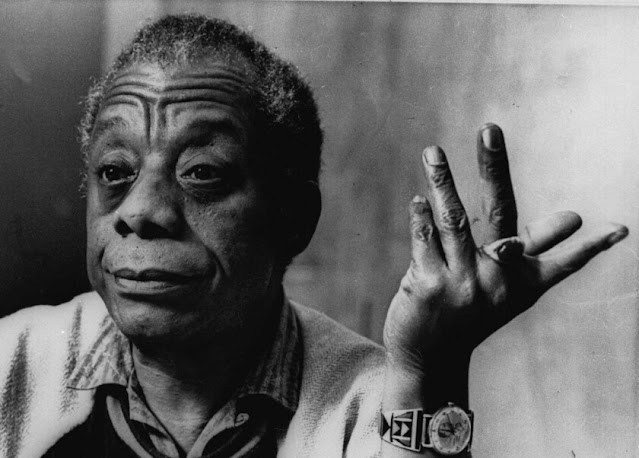

| Nina Simone |

Nina Simone also had wanted to be a concert

pianist, but again she was forced to play jazz and sing in order to pay the bills. So many African-Americans have been denied the opportunity to have classical careers.

|

| Oscar Peterson |

Even Oscar Peterson boycotted this country for years because American concert agents booked him in jazz clubs, while in Europe he filled opera houses. Thank goodness the days of such blatant discrimination have passed, but we must keep up the pressure on concert agents and performing arts venues, as well as symphony orchestras.

*Clara Schumann: The Artist and the Woman by Nancy B. Reich

Comments

Post a Comment