An Excerpt from "Practicing for Love: A Memoir" by Nina Kennedy

In the wake

of the widely publicized sexual-abuse claims brought by violinist Lara St. John against the late Jascha Brodsky, her violin teacher at the Curtis Institute of Music (read the article here), I decided that it was time to share my own story of abuse that took place when I

was a student there.

The kinds of abuse I endured there were verbal and

emotional. The perpetrator was clearly a racist, but I did not have the skills

at the time to handle such abuse. It was devastating when it became clear to me

that my teacher was not going to help me pursue a career, because a concert

career was all I had ever imagined for myself. It had been my parents’ dream

for me, and their mothers’ dreams of both of them. Little did I know that this

one racist, elderly white woman set out to crush their dreams, and to destroy

me in the process.

|

| Nina Kennedy at age 9 |

The year I

auditioned to enter the Curtis Institute of Music there were three openings in

the piano department, and seventy-two pianists came to audition for those three

openings. Before arriving at Curtis I had given my first complete recital at

age nine, and had appeared as piano soloist with the Nashville Symphony at age

thirteen (before an audience of over four thousand).

My first

book – Practicing for Love: A Memoir –

is scheduled to launch this month. This book marks the end of my silence. Here is an excerpt from the book on my time

at Curtis.

From Practicing for Love: A Memoir by Nina Kennedy, ©2019:

"The day the acceptance letter from Curtis arrived, I was

afraid to open it. As long as I didn’t know the results, there was still hope.

The letter was waiting for me in the car when my mother picked me up from the

bus stop that day. I opened it to find that I had been accepted. My mother shed

a few tears and then told me to call my father as soon as we got home. She

actually dialed his number and said that I had something to tell him. When she

held out the phone for me, I yelled across the room 'I was ACCEPTED!!'

He then said to me, 'You’ve just made my... life!'

"Wednesday afternoons, all students would meet in the Common Room of the Curtis Institute for tea poured by the elderly daughter-in-law of founder Mary Curtis Bok. Every time she saw me, she asked what instrument I played and how long I had studied there. And I saw her every week!

My

class schedule was intensive. I had my weekly piano lesson with my primary

teacher, Eleanor Sokoloff, Keyboard Studies and Score Reading with Dr. Ford

Lallerstedt, Music Theory with David Loeb, and Ear Training with Miss Klar.

Having the grand piano in my studio apartment meant that I never had to worry

about finding a practice room. I took advantage of the opportunity to learn

copious amounts of repertoire, including Beethoven's 'Appassionata' and 'Waldstein' Sonatas, Chopin's F minor Ballade, the Tchaikovsky and Brahms D

minor concerti.

I

thought that studying at the Curtis Institute meant that I was well on my way

to establishing a solo career. However, my primary teacher, Eleanor Sokoloff,

had other plans. She made it clear in my first lesson that she would not listen

to any repertoire. She would only hear me play scales, arpeggios, and Pischna

exercises, which were some of the most boring exercises ever written. Mrs.

Sokoloff had a very loud, almost screeching voice that I found to be very

intimidating. Her comments could be quite rude at times. No one had ever spoken

to me this way before. I was quite disheartened at the thought of having this

woman as my teacher for the next four years.

Welcome

to Curtis!

That

year there was a story being whispered among the students about a female piano major

who had practiced and learned the Brahms Second Piano Concerto over the summer.

Her teacher was Mieczyslaw Horszowski. When she brought this piece into her

first lesson of the school year, Mr. Horszowski refused to hear it.

'A woman cannot play this piece,' he

said.

At

the time, the man was eighty-six years old. Did he not know that Johannes

Brahms composed the piece for Clara Schumann to premier and perform? The poor

student had no recourse. There was no one to whom she could complain. One can

only hope that the students at Curtis today are not subjected to such sexism.

That

year Marian Anderson was a Kennedy Center Honoree and would receive the medal

from President Jimmy Carter. The event was being broadcast live from the

Kennedy Center in Washington and Miss Anderson actually called me in my little

studio apartment to tell me to watch. She asked how it was going at Curtis. I

guess she could tell from my voice that I wasn't terribly enthusiastic. She

told me to wear pretty dresses and to keep my chin up. I didn't have the heart

to tell her that I didn't wear pretty dresses.

Marian

Anderson had enjoyed success and fame in Europe in the 1930s and was almost

worshipped as a goddess in Sweden, where she met and sang for famed pianist

Arthur Rubinstein. He wrote in his second autobiography My Many Years just after he had signed a contract with concert

impresario Sol Hurok for a third American tour, 'Suddenly at that point I

thought of Marian Anderson. My enthusiasm for her had had great results. She had

an immediate overwhelming success wherever the managers engaged her on my

recommendation. I told all that to Hurok. "You ought to present her in

America," I said, "I vouch for her triumph. She is the greatest Lieder singer I

have ever heard." He made a sour face. "Colored people do not make it with the

box office," he said in his professional lingo. But he was visibly impressed by

my insistence. He left for Amsterdam to hear her sing and signed a contract the

same night.'

Sol

Hurok secured the engagement for Anderson to sing on the steps of the Lincoln

Memorial before an audience of over 100,000 after the Daughters of the American

Revolution had refused to allow her to sing at Constitution Hall – which they

owned – because of her race. That concert marked the turning point in Hurok's

career.

|

| Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson |

The

year was 1937 and Rubinstein had already noticed tensions and violence

perpetrated by Hitler's Nazis against the Jews throughout Germany, Poland,

Hungary, and Romania. As he lived in France, he himself would be directly

affected by this surge in hatred only a few years later. I don't know if

Rubinstein was aware of the fact that audiences in our nation's capital were

segregated until Marian Anderson's groundbreaking concert at the Lincoln

Memorial. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt used this concert as a propaganda

ploy to solicit 'Negro' participation in and enthusiasm for the

Second World War. After all, how could he justify sending black troops to

defeat the Nazis while racism prevailed at home? Mrs. Roosevelt resigned from

the DAR after witnessing their embarrassing behavior.

Violinist

Fritz Kreisler was on the side of the Germans during World War I, so it should

have come as no surprise that Kreisler played for segregated audiences. In the

1920s there was outrage in the black community of Charleston, West Virginia –

my mother's birthplace – when Kreisler was engaged to give a concert but blacks

were not allowed to purchase tickets. My uncle Howard, who was still a young

boy and burgeoning violinist, was given a ticket and was thus able to attend.

My maternal grandparents, along with other African-American community leaders,

took out a full-page ad in the local newspaper protesting this blatant

discrimination. Kreisler brought his racist leanings to the United States where

racism, segregation, and discrimination were already flourishing but on a

different level than his German anti-Semitism. He was one of a few individuals

who spread their racist filth all over the globe.

When

African-American soldiers liberated the German and Polish concentration camps,

they were praised as heroes by the Jews. But when these men returned to the

United States hoping that their patriotism would grant them equality in their

homeland, they were greeted with the same indignities that they had endured

before they left. My own father told a story [in the documentary film Matthew Kennedy: One Man's Journey] of being mistakenly put in charge

of a group of white soldiers during the Second World War and being responsible

for getting them from Boston to Virginia. He sat panicking for the whole train

ride, wondering what he would do when they reached the Mason-Dixon Line where

he would be required by law to sit in a segregated 'Jim Crow' car. He

continued to panic until they disembarked without incident. But this was the

kind of humiliation American soldiers had to endure well into the 1940s and

beyond.

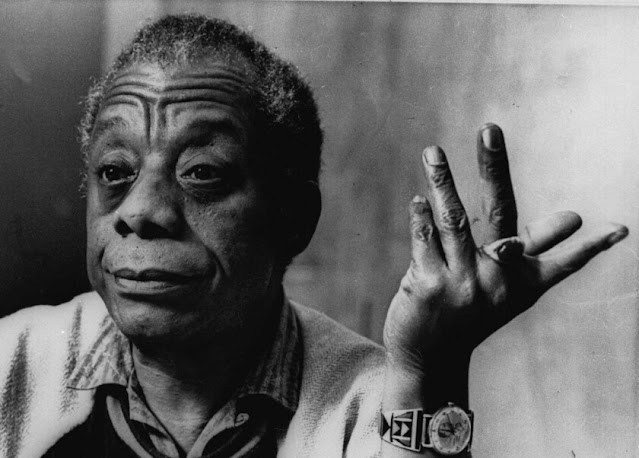

|

| Matthew Kennedy |

Now

the Trump administration and the Republicans are bent on destroying the gains

African-Americans have made over decades. To watch them in action is truly

nauseating, and many of his followers don't even know why they need to hate

scapegoats so much. Such people seem to need to feel superior to someone else

in order to feel secure. They haven't even bothered to figure out why they have

chosen a particular target. It is most unfortunate. But I digress.

I

saw on the Philadelphia Orchestra schedule that operatic tenor Seth McCoy was

scheduled to appear for a concert, so I wrote to him to ask if he'd like to

meet. He invited me to lunch at one of downtown Philadelphia's most expensive

restaurants. We had a lovely chat and a delightful meal. When he saw that

Curtis was getting me down, he became angry.

'Don't

you let those people break you down. They make me sick!' he hissed under

his breath.

|

| Seth McCoy |

He

then gave me the whole story about how some American opera houses refused to

cast him as the romantic lead with a white soprano. His anger surprised me,

since he was a success. My father had never shown such functional, targeted

anger. He would waste so much energy on talking himself out of his anger that

he was totally blocked. Then his anger would spew out in uncontrollable,

dysfunctional tantrums, usually directed at females. I never saw my father go

off on a man.

Sylvia Olden Lee was a premiere vocal

coach who was on the faculty at Curtis. In 1933 she

was invited to play at the White House for the inauguration of President Franklin Delano

Roosevelt. In 1942 she toured with

baritone/film star Paul Robeson as his official piano accompanist, and in 1954

she was hired as vocal coach for the Metropolitan Opera. She coached opera

stars Kathleen Battle and Jessye Norman. Her husband, Everett Lee, was an

internationally acclaimed orchestral conductor who made his home in Sweden. He was the first African American to conduct a Broadway musical, the first to conduct an established

symphony orchestra below the Mason-Dixon Line, and the first to conduct a performance by a major U.S.

opera company. I had heard him conduct the Nashville Symphony before I

left there.

|

| Sylvia Olden Lee |

During

one of my boring lessons of playing Pischna exercises, Mrs. Sokoloff blurted

out, 'That Sylvia Lee has been asking me and the director why you and

Graydon Goldsby [the other black piano student] aren't participating in the

concerto competition.'

Every

year the Philadelphia Orchestra would sponsor a concerto competition for young

artists. The winners would perform with the orchestra.

Mrs.

Sokoloff continued, 'When she goes off the deep end, watch out! I told her

you weren't participating because you weren’t ready.'

Well

part of the reason why I wasn't ready was because you only allowed me to play

scales and arpeggios and Pischna exercises! How dare you?!

Sylvia Olden Lee was reacting to the racism that we encounter every day. I kept

my mouth shut because this woman had complete power over me. But I never forgot

how this white woman felt totally free to disparage this family friend without

fear of complaints or reprimand.

Toward

the end of the school year, Eleanor Sokoloff informed me that she was not going

to renew my scholarship for the following year. In other words, she was kicking

me out. She allowed me to prepare to audition for other faculty members before

the end of the year, but I'm sure she made it clear to them that I was not to

be re-admitted. Since I was preparing a program, she submitted to listening to

repertoire. Thank God! If I'd had to play another Pischna exercise, I would

have passed out. I prepared the Chopin F minor Ballade and the Beethoven

Waldstein Sonata for performance. Mrs. Sokoloff agreed to listen to my program

one last time before I played for Horoszowski and Bolet.

When

I finished the Chopin, she said, 'I could kick you in the stomach!'

'Excuse

me?'

'I

could kick you in the stomach! If I had known you could play like that, I never

would have revoked your scholarship.'

I

couldn't believe what she was saying to me.

She was the one who had refused to listen to any repertoire all year. And

now she's shocked that I can play?!

'Well

it's too late now. There's nothing I can do,' she said.

I

left her studio hoping that I would never have to look at her old, wrinkled

face again. Later I would learn that she had made a habit of kicking young

girls out of Curtis. She had ruined so many careers and no one ever questioned

her actions. My mother had even come to ask her face to face exactly what the

problem was. I observed them from a distance in the Common Room. My mother told

me that all Mrs. Sokoloff could talk about was what I wore. She was a pro at

this so she totally dominated the conversation. I was quite surprised that my

mother was so quiet.

I

had read in Arthur Rubinstein's My Young

Years of his encounter with a teacher in Berlin who was so embittered that

he set out to sabotage careers of young pianists. Whether it is conscious or

not, such creatures exist and school administrators should be very careful when

hiring teachers who literally hold the futures of these young artists in their

hands. Eleanor Sokoloff had been a fossil dating back to the days of the Curtis

founder, Mary Curtis Bok. Most of the people of that generation did not believe

in civil rights or equality for African Americans. Such people got their kicks

out of taking on a student just to destroy him or her, and they know full well

that the shame of being kicked-out would force the victim to keep his or her

mouth shut. It took a lot of work for me to overcome Sokoloff's mistreatment

and verbal abuse. Unfortunately, I have heard that she set out to ruin many

more careers. As I write this, she is over one hundred years old and still

torturing students.

Mrs.

Sokoloff did have some students who weren't necessarily so talented, but she

liked them nonetheless. I learned later that these students had wealthy parents

who often wined and dined both of the Sokoloffs. Her husband Vladimir was also

on the faculty and supervised much of the chamber music at Curtis, so I saw him

there often. He was very chummy with then director John de Lancie. These

parents often paid for private lessons and also made of habit of presenting

Mrs. Sokoloff with expensive gifts. Since my parents could not afford to play

this game, it was clear that I was going to have to find someone who could.

|

| Nina Simone |

Years

later, I would learn of the heartbreak suffered by pianist / songstress Nina

Simone inflicted by the Curtis Institute of Music. She came with her family to

audition for admittance to Curtis, but was rejected. As a result, she was

forced to take a job in a nightclub in Atlantic City to support her family. At

first, she played the piano wearing concert gowns, but the manager forced her

to sing and threatened to fire her if she didn't. She was an extremely talented

pianist and had said that she wanted a concert career. The National Association

of Negro Musicians gave her some support, but it was not enough to launch a

classical career in a field where whites made all of the decisions. It should

come as no surprise that she sang The Blues so well."

In Lara St.

John’s case, she was told by then dean Robert Fitzpatrick to keep quiet and that no one would believe her. In my case, I didn’t even know how to complain, never

mind to whom. I never would have had the courage to walk into the director’s

office and file a complaint. What would I have said? “My teacher is a racist.”?

I knew I had no evidence, no hidden tape recordings, no letters or notes. It

would have been my word against hers, and she certainly would have denied it.

I hope that

young students today know that they can go to the NAACP, or to a students’

rights organization, or a women’s advocacy group. Racism is still pervasive in

the classical music field, and I pray that today’s students are armed with the

resources they need to fight the injustices they face. Speak out! Tell the

truth. And don’t be afraid. We believe

you!

Nina Kennedy is a world-renowned concert pianist, orchestral conductor, award-winning filmmaker and television talk show host. She holds a master's degree from the Juilliard School and served as conducting apprentice under Kurt Masur during his tenure as music director of the New York Philharmonic and l'Orchestral National de France. She has performed and resided in Amsterdam, Cologne, Paris, Prague, and Vienna. She produced the award-winning documentary titled Matthew Kennedy: One Man's Journey - featuring her father, former director of the Fisk Jubilee Singers - which was selected and screened at international film festivals worldwide.

* Practicing for Love: A Memoir is published by RoseDog Books ($24 plus S&H). To order a copy, email your request to info@infemnity.com.

Comments

Post a Comment