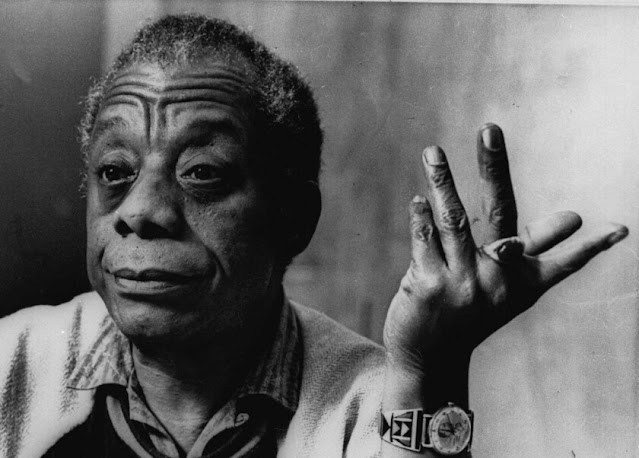

James Baldwin's Brotherly Love

While sitting in the audience for a screening of the documentary on James Baldwin titled The Price of a Ticket during the James Baldwin Centennial Convening at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, I was forced to make a connection between Baldwin's words and a review of my recent concert in Mexico City. In the film, Baldwin says at a poignant moment:

"It is not a romantic matter. It is the unalterable truth. All men are brothers. That's the bottom line."

For a man who had been on the receiving end of such hatred, such discrimination and prejudice, that is quite a courageous statement to make.

A few months ago I was invited to give a concert as part of the 27th Festival Internacional de Piano en Blanco y Negro. This was my first big concert since COVID, so I had quite some anxiety over whether or not I'd be able to pull it off. Fortunately it went very well; I received a standing ovation and was called back for an encore. The next day a review appeared online by Pedro Helguera. The review was in Spanish, so the translation was pulled from the closed captioning. Toward the end, Helguera says:

"Nina Kennedy's concert was an unforgettable experience not only because of the impeccable technique that I am boasting about but also because of the emotional connection she achieved with the public. The audience did not need to interact with her, but we had a total connection. We all became brothers while listening to it. Each piece was carefully performed with great attention to detail to the style of each piece from romanticism to African-American songs."

To read the entire review click here.

I had no idea that a piano recital had the power to make men feel like brothers, and I am extremely grateful to Pedro Helguera for his effusive praise. But to hear Baldwin speak the words two weeks later that all men are brothers - whether they know it or not - is especially meaningful at a time when innocent civilians are being killed by the likes of Vladimir Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu. The news today is frightening, and it is refreshing to be reminded that Baldwin - as angry as he may have been - still believed in brotherly love.

When I arrived at the Schomburg for the first day of the Convening, in my gift bag was a copy of Baldwin's The Amen Corner - a play I had never read. At the end of the first day, after a "Coda" presented by poet Samiya Bashir titled "A Lover's Question," the moderators invited people in the audience to come to the microphones to share closing thoughts or comments. There had been Q&As after each panel, that day and usually there were long lines of people waiting to ask questions. Well this time, there was no one standing at the mic. One of the moderators even commented that this was a first in Schomburg history, that the mics were open for comments and no one was standing there. I waited a few seconds, saw the spotlight and the photographers waiting, then stood up and walked to the mic.

At first I said that I wanted to invoke the name/spirit of Diana Sands. Most people know her as the actress who portrayed "Beneatha" in Lorraine Hansberry's A Raisin in the Sun. Those of us who were in the audience for the screening of The Price of a Ticket had just witnessed a clip of her performance in Baldwin's Blues for Mister Charlie, in which her character begs God to let her be pregnant, instead of losing her mind.

In the film we also heard Baldwin's boyfriend, Lucien Happersberger, talk about how he and Jimmy had fled from Paris to a tiny, primitive village in Switzerland where Baldwin finished writing Go Tell It on the Mountain. (When they met in Paris, Lucien was 17; Jimmy was 24. Lucien was also white.) He spoke of how they both took the manuscript to the post office and mailed it off to the publisher.

Baldwin famously said that he moved to Paris to save his own life. He felt that if he had stayed in the United States, he would end up "in prison or dead." When I moved to Paris, it was primarily because of an exceptional wine year. At the time, my Austrian lover and I both wanted to get away from Germany, and we also wanted to improve our French. As an African-American classical musician, of course I felt the need to escape from American racism, which was why I was in Germany in the first place. I didn't think I went to Paris to write, but there's something about hearing and speaking French that enhances one's English. I ended up spending most of my time writing, in addition to enjoying the wine.

In the film, what Happersberger did not mention was that - in a moment of feeling closeted, or tired of being called Baldwin's "secretary" and "personal assistant" - he married Diana Sands while she was working in Blues for Mister Charlie on Broadway.

I shared all of this with the audience in my comment, and the hall was filled with the sounds of "Umhmm!" and "That's right!" from the people. I was pleasantly surprised to have my own "Amen corner" there at the Schomburg.

That marriage broke James Baldwin's heart. He ended up in the hospital with various infections and ailments soon afterwards. The marriage only lasted for two years. He and Lucien eventually reconciled, but we can only imagine the bitterness that Baldwin directed toward Diana. It is always easier - after all - to direct one's rage toward someone who is smaller and weaker than you.

During the various panels, several had spoken of how Jimmy was drinking and smoking himself to death, and ultimately lost his battle with cancer at age 63. Meanwhile, I was the only one to mention that Diana Sands lost her battle with cancer at age 39. Happersberger had been her only husband.

In the preface of The Amen Corner, Baldwin wrote of his struggles to complete Go Tell It on the Mountain, which he said took him 10 years to write. He wrote of borrowing money from Marlon Brando, and going to Switzerland to finish the writing. But not once did he mention Lucien Happersberger! Granted, the homophobia of the day was extreme, and he was limited in what he could write by various white publishers and agents. The multiple slights and omissions certainly took their toll on Lucien.

Ultimately, the love between "brothers" prevailed, while Diana was left to feel used, exploited, and discarded.

That night, I couldn't help thinking of Diana Sands when I read Baldwin's words in the preface of The Amen Corner:

"[Sister Margaret] is in the church because her society has left her no other place to go. Her sense of reality is dictated by the society's assumption, which also becomes her own, of her inferiority."

To close my comment, I said, "Diana Sands was a sistah who struggled and never received the praise she deserved." [More 'Amen's] "So in this moment I simply wanted to say: Diana Sands, I praise you!" My comment received a round of applause.

I had begun this essay that night, but the next day, after a panel called "James Baldwin and the Intimacy of the Essay" with Jacqueline Woodson and Edwidge Danticat, this essay expanded into the piece your are reading now.

|

Comments

Post a Comment